By Jireh Li

Foreword

Through combining academic analysis, empirical research and China VC business practitioner insights, this paper puts forward the concept of “China Ecosystem VCs,” and examines it from the angles of a Platform-based VC, Resource-based VC, Composition-based VC, and a Dynamic-model. It demonstrates their emphasis on leveraging “ecosystems” to actively create tangible, multi-faceted value. By inventing, de-emphasizing, or moderating certain processes of the Venture Cycle, it proposes that Ecosystem VCs are able to better navigate and use the challenges of the venture business to their advantage. China’s Ecosystem VCs suggests that China is going beyond the traditional playbook that Western VC counterparts have adopted for many years. It is a manifestation of China as a powerhouse, paving the way for new paradigms and breakthroughs in the venture business. This article was first published as a Cover Story in the Tsinghua Financial Review January 2020 Issue (in Chinese), and in FoF Weekly and Medium (in English).

Introduction

Technology empowers business, capital emboldens entrepreneurship. Over the past four decades, China has come to figure prominently in the VC industry. The burgeoning China VC hub today rivals that of Silicon Valley. Despite its growing prominence, theoretical advancement or empirical investigations about VC business models, or specifically about China venture, is relatively modest in scope.

This paper establishes the key characteristics of a new kind of VC the author has coined as “Ecosystem VCs.” Ecosystem VCs refer to the VC’s use of its “ecosystem advantages” to strengthen the complete processes of fundraising, investing, portfolio management and exits, and uses the its resource networks to actively promote the development of its invested enterprises, so as to create tangible and multi-faceted value, to benefit itself, its ecosystem, its portfolio companies, and society. Compared with the classic practices and traditional theories stemming from the U.S. VC industry, China’s Ecosystem VCs demonstrate innovative characteristics in implementing the Venture Cycle. This Framework is not only widely recognized by global limited partners (hereinafter referred to as “LPs”), but also suggests that China is going beyond the traditional playbook that Western VC counterparts have adopted for many years.

The Key Categories and Characteristics of China’s Ecosystem VCs

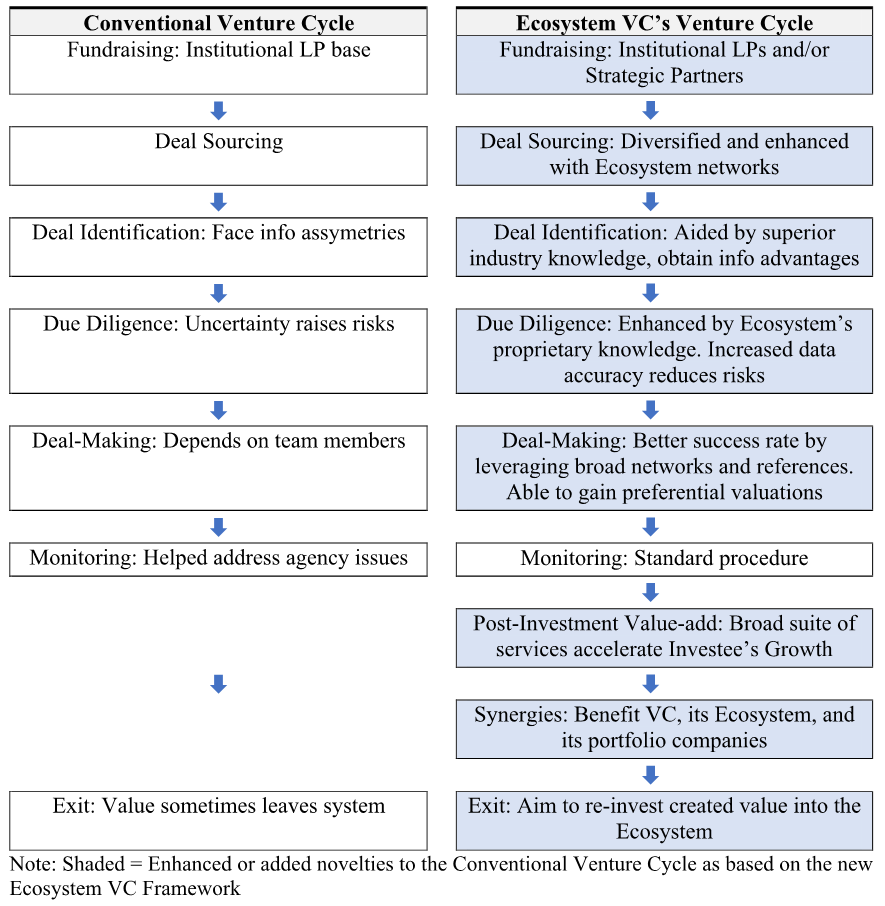

The earliest “Venture Cycle” was proposed by Professor Josh Lerner from Harvard University and Paul A. Gompers. According to traditional practices, a VC starts by fundraising from LPs, proceeding on to make investments through sourcing, diligencing, investing, monitoring, and finally, exiting and distributing capital to LPs. The cycle renews itself with VCs raising subsequent funds. At the same time, VC investments are associated with the basic challenges of “informational asymmetries,” “illiquidity,” and “high risk.”

As proposed by the author, Ecosystem VCs are venture capital firms that build and thrive on an ecosystem of their making. They adopt a method of value-creation that actively allocates capital and resources, and/or redirects them in a way that increases productivity across the board, with the goal of fast-tracking growth in start-up’s. This helps the VCs themselves de-risk and potentially enjoy better chances of achieving outsized returns. Based on current observations in the Chinese VC industry, they can be divided into: Platform-based VC, Resource-based VC, and Composition-based VC.

Platform-Based VCs

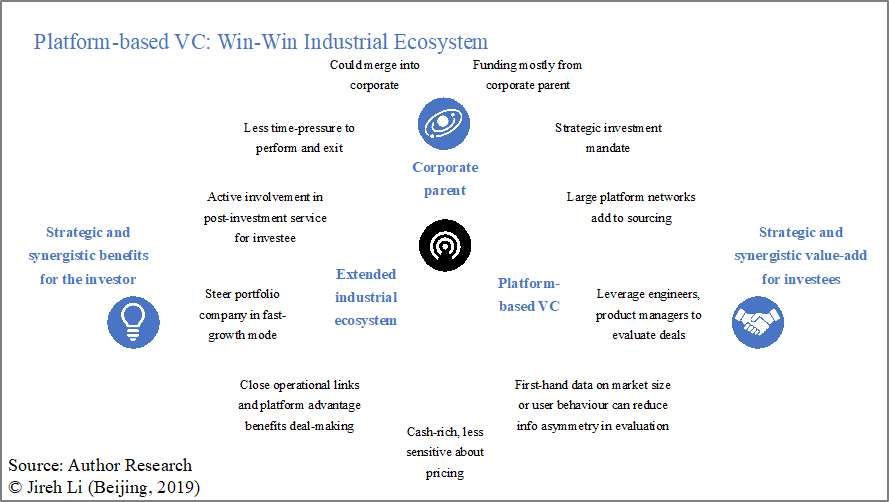

Platform-based VCs thrive on their “platform” strengths, and are generally portrayed as strategic investment arms of large Internet enterprises in China. Their extensive business lines create an “industrial-centric platform.” Through this industrial layout, Platform-based VCs integrate business, operational, and strategic synergies for its investees, who in turn complement the corporate’s product offerings and strengthens its market influence.

A key characteristic of Platform-based VCs is that their platform’s strength helps improve the efficiency of capital. By virtue of being a leading corporation in respective fields, these VCs have an “unequal advantage” in industry discernment, meaning more accurate or deeper insights over peers about a marketplace, customer attributes, or supplier preferences. For example, Tencent (HKSE: 0700), Alibaba (NYSE: BABA), and DiDi Taxi can leverage in-house product managers and engineers to identify and evaluate founders, technologies, or product attractiveness. This helps reduce the uncertainty and “information asymmetries” inherent in due diligence.

These VCs demonstrate strong ability to promote business cooperation within the broader platform. Take Xiaomi’s (HKSE: 1810) strategic investment department as an example. Its extensive IoT and AI Ecosystem provides its investees with the ability to overnight tap into a community and customer base of 260 million+ Mi-fans, gain access to distribution partners, not to mention other integrated cloud computing, PR and HR support. Platform-based VCs have significant advantage in attracting entrepreneurs, winning deals, and negotiating terms. It can connect investees to valuable resources in an accelerated manner, such as sharing in Tencent’s traffic through WeChat Wallet, accessing local and international “2B” or “2C” customer channels through Alipay, Taobao, and Xiaomi’s online store, receiving big data insights, CRM (Customer Relationship Management) software, or logistics expertise (e.g., through gaining access to Alibaba’s Cainiao logistics platform).

One of the biggest differences with the conventional VCs is that the post-investment monitoring goes beyond basic “board participation” or “advice.” Once identified as value-accreting, Platform based-VCs actively steer a portfolio company into fast-growth mode, and take an integral approach in the start-up’s development and integration into the parent’s networks. It can provide its investees with access to the corporate parent’s resources and assets, help it connect to an extended network of experts, engineers, provide brand endorsement and potential for continued capital support.

In addition, Platform-based VCs go beyond financial gains to seek a strategic angle to optimize its industrial layout, seek strong resource integration and industrial-linking capabilities. For example, Tencent’s has enriched its WeChat’s services and channel revenues through its O2O (online to office) investment layout; Xiaomi has over 151 million smart devices connected to its platform with jointly owned IP and user data.

This two-way post-investment value-creation for both investees and the investor collectively forms a virtuous, win-win circle. It can help introduce new business units or novel technologies for the parent, realize a degree of cost-savings, hedge business risk, augment the corporate’s market positioning, enhance and complement its own innovative abilities, and accelerate the growth of existing business units. This way, the Platform-based VCs can attain “ecosystem synergies” and realize exclusive or otherwise unattainable business collaborations.

Resource-Based VCs

Resource-based VCs are huge resource magnets that thrive on the strengths of their “proprietary resources.” They are born out of a long-time evolution (10+ years) of a usually very successful franchise. In other words, they do not start as “Ecosystem VCs.” Instead, long-term investment experience, capital advantages, managerial expertise, premium brand value, and vast networks, when structured and integrated overtime, let them claim their own standalone ecosystem, which is difficult to replicate. This allows it to operate in a different stratosphere from other VCs.

Key characteristics of Resource-based VCs revolve around a strong capital base, and knowledge and expertise to invest across multiple stages (horizontal integration, with early and growth investment abilities) and multiple sectors. Examples include Sequoia Capital China, GGV and Hillhouse. Do note that Resource-based VCs are able to evolve into independent ecosystems because the VC industry is heterogeneous in nature, meaning entrepreneurs are “discriminating” by nature, as not all VC funding is viewed the same. Moreover, while the exact mix of resources vary, the key is that they enable Resource-based VC to simplify the Venture Cycle to their advantage with economies of scope, and turn market inefficiencies into their base of market power.

For the VC itself, a well-endowed capital base relatively-speaking provides more opportunity to scout-out or invest in emerging market trends ahead of competitors. Take Sequoia Capital China as an example, it can take positions in companies across multiple rounds within the same “investment track,” which helps hedge, reduce risk, and maximize sector coverage. In the PC-Internet and mobile/e-Commerce era (circa 2006-2009), mobile Internet and O2O era (circa 2010-2012), sharing economy, consumption upgrade and Internet finance era (circa 2012-2015), Sequoia China’s investments created a cohesive portfolio and “investment layout” that developed into a “sector-focused ecosystem” of its own.

Resource-based VCs actively bring value-creation to its portfolio companies, particularly the ability to invest long-term across multiple stages of a company’s development. An example would be English language start-up VIPKID, which Sequoia China invested into four times continuously (A to D rounds). Precise post-investment services and effective risk controls can help Resource-based VCs reduce its portfolio risk. For instance, it can provide a wide range of CEO, CFO, CTO, and other industry contacts for its investees, plus extensive post-investment support and operation know-how.

Resource-based VCs are not only adept at managing their proprietary resources. They are skilled at leveraging their “combinative capability” to synthesize, combine, and apply current and acquired knowledge in order to gain a competitive edge, transforming market inefficiency into its basis of market dominance. Every Sequoia China team member can access and systematically learn from the global franchises’ past successes or mistakes, with information in an internal database dating back to 1972. Overtime, this helps the Chinese teams garner, absorb, and collectively synthesize knowledge regarding management, investment methodologies, technology, history or other global learnings.

In short, the possession of self-owned and accumulated resources enables the Resource-based VC to conceive and implement strategies designed to improve its performance, and use economies of scope to reduce resource redundancies, enlarge the value of investing, and maximize potential financial returns.

Composition-Based VCs

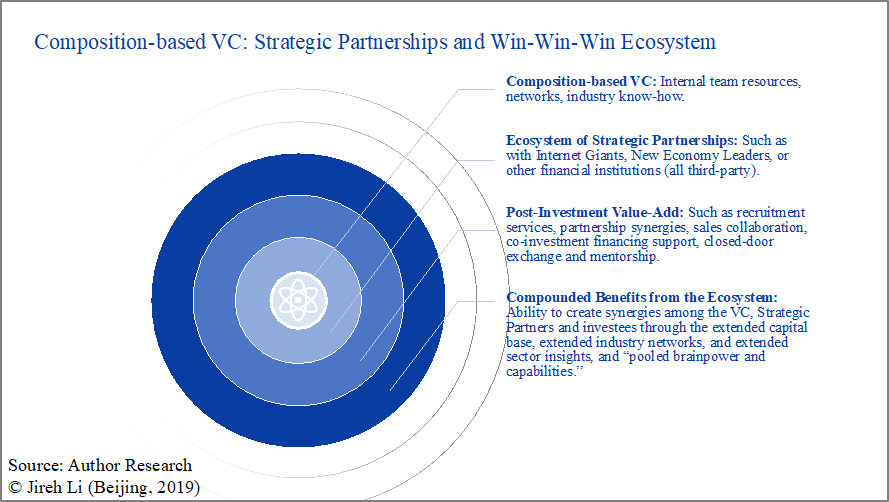

Composition-based VCs are independent venture firms who thrive on their arrangement of “strategic partnerships.” They create, combine, and build upon relationships in a novel approach, and through formal or informal arrangements, amalgamate and incorporate external resources and expertise as part of its product offering. Composition-based VCs typically establish mutually-beneficial business partnerships with leading enterprises, mostly tech giants, new economic leaders or other financial institutions (all third-party).

Through combining industrial and financial capital, Composition-based VCs integrate extensive industrial resources, insights and capital into its “pooled brainpower and capabilities.” This provides a broader set of competitive advantages that go beyond the internal teams’ strengths, and enhances all processes of fundraising, investing, portfolio management, and exits for the VC.

As a case study, Source Code Capital shows how its ecosystem of partnerships create a competitive edge. Its compositional competence via Code Class helps it identify, integrate, and combine resources both externally and internally. Code Class’ key members include enterprises such as Meituan-Dianping, ByteDance, and Beike (aka HomeLink). The combinative strategic abilities integrate domain expertise (technology, brand, products, capital, services, brainpower), sustains quality sharing, helps start-ups and Internet giants connect, and gives full play to the power of market resource allocation. Compared to traditional VCs, Composition-based VCs can better leverage strategic partnerships for brand endorsement, information and deal-making advantages.

For portfolio companies, Code Class brings a network effect, enabling Source Code to integrate industrial and financial capital into its post-investment platform. Indeed, Composition-based VCs are good at using their extended networks to create technological or business collaborations, talent introductions, strategic and operational advice, or comprehensive financing assistance. The network effect provides entrepreneurs with customized contacts to promote diversified and in-depth cooperation among parties. This can help the invested enterprises and strategic partners carry out technology and sales cooperation, follow-up financing, enjoy candid sharing regarding entrepreneurial challenges and related solutions, and share in the deep resources exclusive to leading enterprises. All this helps accelerate the development of the VC’s investees and augments potential investment returns.

At the same time, through the effective arrangement of the composition-ecosystem and its resources, products and services, Composition-based VCs can cultivate strategic information distribution and exchange, stimulate and achieve multi-dimensional cooperation and benefits. Particularly for its strategic partners, this may provide a continuous source of information about novel technologies or new start-up ideas. It may generate additional synergies along the same industry chain, or even provide future acquisition targets. By effectively arranging and integrating its combined partnerships, capabilities, products, and services, Composition-based VCs aim to achieve a compounding effect for all parties involved.

Comparing Ecosystem VCs with the Conventional Model

As based on empirical research, surveys, and first-hand interviews with over 81 top-tier VC and PE firms in China, placement agents and leading LP institutions in the world (representing 178+ seasoned professionals and executives): Ecosystem VCs enhance the Conventional Venture Cycle by elevating, emphasizing, and addressing various processes more intelligently. The unique characteristics of Ecosystem VCs and the virtuous circle of multi-faceted value created provide them with comparative advantages over Conventional VCs (see Table 1). While not definitive, this qualitative and quantitative comparative analysis lends a new perspective to the Venture Cycle and underscores new competitive and innovative methods for VCs to back and grow start-ups.

In the pre-investment phase, Ecosystem VCs can use its “ecosystem capabilities,” such as faster and more accurate access to information about a market, technology and product, and convert uncertainties and information asymmetries into sourcing, diligence and deal-making advantages. In the post-investment phase, they proactively help companies grow faster by unlocking operational, industrial and business synergies from their ecosystem. They can provide more extensive and diversified value-added services, make full use of their “ecosystem advantages” and network resources to fast-track their portfolio growth, with the goal of potentially obtaining outsized returns. This is a major difference from conventional VCs, who mostly passively monitor their investments.

Table 1: Comparison of the Conventional and Ecosystem VCs’ Venture Cycle

Challenges and Evolution Trends for China’s Ecosystem VCs

Of course, there is no denying of the potential drawbacks Ecosystem VCs have, and each category has its respective shortcomings and limitations. An overarching constraint is heavy reliance on human relationships and aligned interests in order to sustain, maintain, and grow the ecosystem. Platform-based VCs may deter other strategic investors, and limit the investee’s future potential to form new partnerships. Resource-based VCs need to continually supplement its capital, team and brand “resources,” which by definition can be depleted overtime and requires replenishing. Further, can cumulated knowledge be consistently shared, absorbed, and synchronized among new and old team members, and when do its economics of scope run into diminishing returns? Running a large team and well-capitalized firm consistently well carries high demands on leadership and managerial skills.

For Composition-based VCs, the key issue is whether chosen strategic partnerships are sustainable and accretive long-run, for compositional advantages seldom hold permanently. Coordinating external partners over the long-term can become costly, and if their ambitions or preferences change, it poses additional challenges to management to maintain and deepen alliances. If Clayton Christensen’s idea of “disruptive innovation” persists, another challenge is the ability of Composition-based VC’s to manage or transition networks, for when, and if, their own portfolios start to challenge the businesses of their initial strategic partners.

Given these challenges, the author believes that there may be a fourth category of Ecosystem VCs, the “Dynamic model,” which completes the Framework (Figure 4). Among multiple variations, it is most conceivable to see the Composition-based and Resource-based VC models converge, as the former bolsters internal strength, and the latter starts to look outside for industrial alliances. The former has the highest degree of “Ecosystemization” with the most external ecosystem origins, but in the long-run needs to bolster and strengthen its internal competencies. While the latter is the most “closed loop,” in the face of increasingly closer linkages between Chinese Internet enterprises and the VC industry, it may consider reinforcing or strengthening external alliances.

Other variations are possible, such as “backward evolution” from Composition-based into Platform-based, by reducing the number of strategic alliances. Platform-based VCs may meander away from their corporate parent into more Compositional-arrangements as well.

By creating and defining a new Ecosystem VC Framework, offering a blueprint of four categories of Ecosystem VCs, and proposing comparisons between conventional and Ecosystem VCs, this comparative study shed light on how the venture business can be done differently, and adds scholastic understanding on the China venture industry. Apart from suggesting alternatives to existing theories, it lends insights into the evolution of a dynamic China venture landscape through time and history, and opens up new subjects for future research, discussed as follows.

Significance of China’s Ecosystem VCs and Future Implications

Looking back, the China venture industry has continuously undergone multiple reshufflings. In the mid-2000’s, core competencies of China VCs shifted away from Western best practices and a generalist approach, to a focus on localized decision-making, and competing on domain-expertise and stage-focuses. In the mid-2010s, the flurry of “spin-outs,” break-up of global VC franchises, increasing horizontal integration of established VCs, and increasing influence of Internet giants, gave way to the emergence of this Ecosystem VC model. The question now is: Where does the industry go from here? Will Ecosystem VCs become mainstream in China?

Indeed, Ecosystem VCs have emerged as a new competitive force in China, and more and more Chinese VCs will develop in that direction in the quest for differentiation. However this does not imply they will become so mainstream as to replace the conventional model, nor do LPs need to suddenly restructure their entire China portfolios. It would be prudent for LPs to distinguish between story-telling, and firms that are truly able to monetize their ecosystem. Becoming an “Ecosystem VC” requires a unique set of conditions, keen organizational effort, and a specific kind of managerial mentality. It is not for everybody.

Second, post-investment services are an increasingly important core competence. Forerunners who can professionalize post-investment offerings can enjoy many dividends before such services become too commoditized. This is likely one of the biggest differences with U.S. venture, where there is relatively less emphasis on post-investment support. Whereas in China, many VCs currently trend in this direction and regard post-investment services as a have-to-have. In go-forward fund diligence, it would be worthwhile for LPs to evaluate the breadth and depth of these services, and how it tangibly de-risks funds or accelerates company growth. It’d be interesting to assess the exact correlation between post-investment value-add and ultimate fund performance, an area that can be better evaluated as we have more data in 8-10 years.

Third, depending on LP reactions, these developments will likely bring about a major reshuffling of the Chinese VC industry in the coming 3-5 years, as the balance of power oscillates between conventional and innovative approaches of doing venture. This ups the ante for Chinese Venture Capitalists to not only be great at investing, but to think ahead about management and organization capabilities.

Fourth, this study recommends cross-pollinating the Ecosystem VC Framework to asset classes like PE or healthcare-focused funds. It poses a research agenda for further studies, such as, the reasons giving rise to Ecosystem VCs, cost-benefits in post-investment services, cultural influences in VC models, the impact of Ecosystem-models on performance, and related behavioral finance and organization behavior topics.

Finally, China’s Ecosystem VCs are emblematic of the progression and evolution in the Chinese economy and in entrepreneurship. It is a manifestation of China as a powerhouse, paving the way for new paradigms and breakthroughs in the art of venture investing. Just as Foreign VCs brought in an adaptation of Western management practices in the early 2000’s, perhaps Ecosystem VCs can now serve as a representation of “Chinese Insights” – and open up a new forum for exchange on Chinese ingenuity, management ideals, and innovative methods – from the East back to the West.